Change is difficult, and we live in a fast-changing world.

Organizations around the world are constantly under pressure to adapt to new conditions, new technologies, and greater expectations from consumers surrounding the social impact they should be creating.

To help manage this challenging environment, firms large and small have adopted the practice of creating a Theory of Change to guide them through the transformation process. In fact, according to the Innovation Network, the majority of organizations around the world (58%) currently use a Theory of Change or similar logic framework when implementing a new program.

Yet, despite the increasing popularity of Theories of Change, effective transformation remains extremely difficult to achieve. The Harvard Business Review states that “the brutal truth is that 70% of organizational change initiatives fail,” while an IBM report titled Making Change Work…While The Work Keeps Changing summarizes the problem as follows: “The gap between the magnitude of change and the ability of organizations to manage it continues to widen.”

Why is this?

In this article, we suggest that any effective impact program requires a focus not only on the mechanics of change - the program’s goals, activities and outcomes - but also on the process of change. This means caring about the personal growth and development of everyone involved in the change program.

What is a Theory of Change?

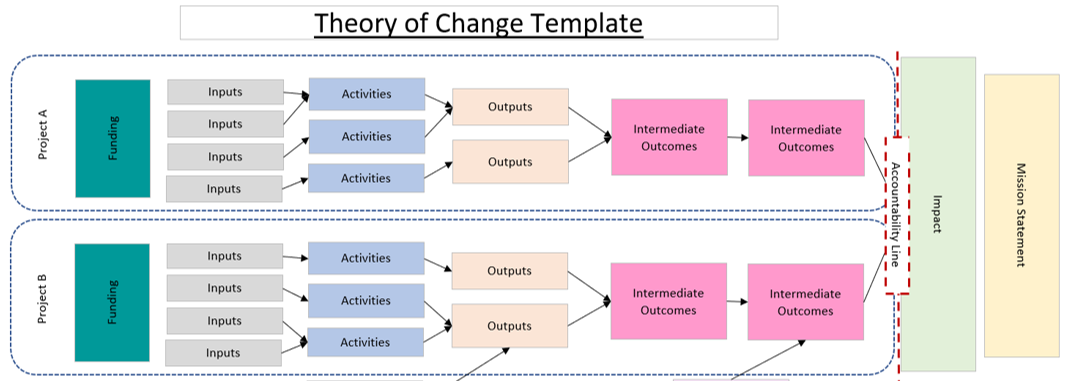

A Theory of Change is a logical framework that defines how a new program is expected to lead to a specific change, either within a particular organisation or broader society.

The official method for building your Theory of Change follows a six-step process, resulting in a visual description of why a particular intervention will be effective through a series of cause-and-effect relationships (usually revealed through a process of ‘backwards mapping’). The result of this process is the creation of a logical framework (also called a logframe): a planning tool that consists of a detailed matrix showing the project’s goals, activities and anticipated outcomes.

Defined by the Center for Theory of Change as “a comprehensive description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context,” the purpose of these logical frameworks is to underpin the change process by providing clear answers to the following questions:

- What do we want the program to achieve?

- What must we do to achieve the program goals?

- How do we know that the program is working?

Also known as ‘intervention logics’, developing a Theory of Change is an “integral part” of the United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) process. In the words of the UN, a Theory of Change can bring “improved clarity and quality to the process of program design and implementation using a simple, flexible methodology.”

Life is not a logframe

The purpose of a Theory of Change is to guide a transition to a new situation by providing a clear map charting exactly how the change process will occur.

However, there is increasing evidence that following this approach too strictly may be limiting in the long-term – and perhaps even counter-productive. The State of Evaluation report from the Innovation Network shows, for instance, shows that “44% of organizations have revised their logic model/theory of change in the past year.”

The main reason for this is that the rigid framework of the Theory of Change can be too prescriptive to accommodate the nuances and vagaries that are always involved with genuine social transformation. Life is not a logframe – and the straight lines and neat causal relationships that form the backbone of most Theories of Change are often insufficient when confronted with real-life social complexity.

We see these thoughts expressed by Craig Valters in an Overseas Development Institute whitepaper titled Theories of Change: Time For A Radical Approach To Learning In Development, where he emphasizes the inherent “messiness” of social change. Likewise in the research of Rosemary McGee and John Gaventa, who state that: “Theory of Change approaches must acknowledge that social contexts and processes are always in flux, with emergent issues, unforeseen risks and surprises arising throughout.”

According to Valters, if Theories of Change are too inflexible, they may “reinforce and mask the problem they aim to resolve.” This idea is supported by Brent Gleeson (writing for Forbes magazine), who claims that overly-prescriptive change programs can lead to “discouragement”, “cynicism” and what he refers to as “change battle fatigue” amongst the very people who are accountable for their implementation.

Changing our attitude to change

So how are organizations meant to thread the needle between Theory of Change frameworks that provide solid measures of program accountability, and the need for open-endedness and flexibility when it comes to implementing programs of social change?

Here, the research of Isabel Vogel (for the UK Department of International Development) is particularly helpful. Her findings indicate that where most Theories of Change go wrong, is that they focus on the framework simply as a change product – and not a simultaneous change process. As she explains, “The strong message from the contributors to this review is that theory of change is best seen as theory of change thinking… It is both a process and a product.”

These insights allows us to see that for meaningful change to occur, it requires commitment to both the immediate goals and objectives of the change program (its strategies and KPIs), as well as the deeper, underlying process of change – which can be “messy”, non-linear and requires genuine personal growth as challenges are encountered, problems are solved, and setbacks are overcome. As the American writer John Maxwell once said: “Change is inevitable. Growth is optional.”

By taking this perspective, we see the true value of the change process not as a map providing didactic directions, but instead as a “a compass for helping us find our way through the fog of complex systems” (Duncan Green, Oxfam).

This paradigm shift – the difference between seeing change as a compass, rather than a map – is often referred to as the difference between a ‘fixed’ or ‘growth mindset’, a term popularized by researcher Carol Dwek. In Dwek’s words, “A growth mindset means that you thrive on challenge, and don’t see failure as a way to describe yourself but as a springboard for growth and developing your abilities.”

Research shows that this approach can be more resilient than the rigidity of ‘fixed’ mindsets when challenged by the “fog of complex systems” that attends social change programs. Dwek asserts that when “companies embrace a growth mindset, their employees report feeling far more empowered and committed” – a healthy antidote to the “cynicism” and “change battle fatigue” discussed earlier.

How can we help?

As an innovation studio that prides itself on making a difference in the lives of youth, Bon Education understands that meaningful change must be dynamic and process-driven.

Our impact programs are geared towards growth. We program for continuous learning, the ongoing expansion of knowledge and skills and the ever-increasing appetite for new challenges, and we use agile program metrics to ensure that our program KPIs are being responsively and effectively delivered.

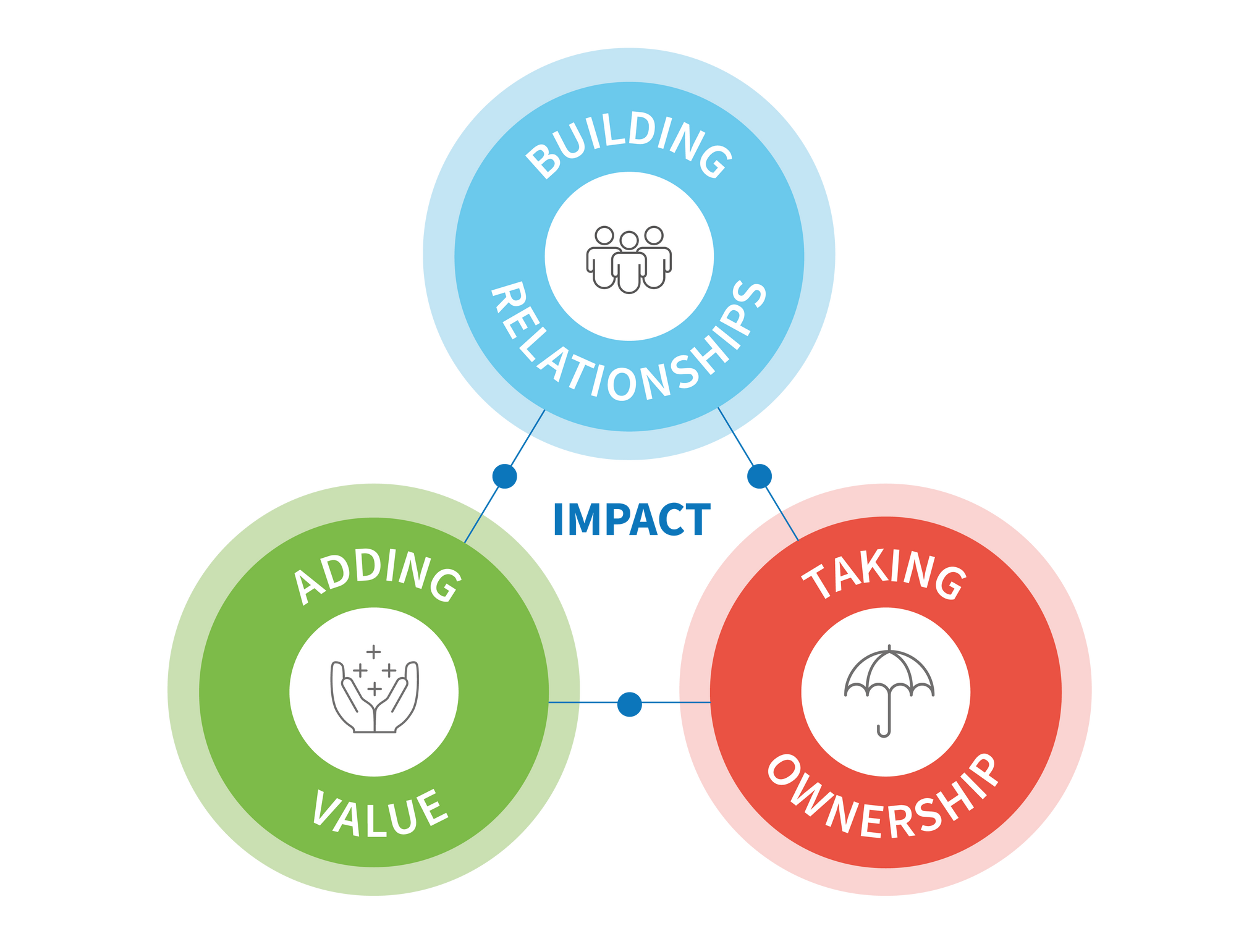

We've created our own Bon Compass to provide orientation during the development and implementation of our impact programs. The Bon Compass applies to program creators, implementers and participants and it can be used to navigate and guide decision-making, especially during periods of intentional change.

- Taking Ownership: Allowing all participants to take responsibility for the goals of the program and the change process.

- Adding Value: Ensuring that everyone involved in the program is empowered by the change.

- Building Relationships: Supporting participants to grow within the change process.

Contact us to learn more about how we create impact through our youth empowerment initiatives, employability programs and workforce readiness bootcamps.

Programming for the personal (and professional) growth and development of everyone involved is the only way to ensure that the process of change is empowering in the long term. When planning your next impact program, remember that an orientation towards growth is as important as the direction of travel described by your Theory of Change.

Change is inevitable. Growth is optional.”

— John C. Maxwell